Fulbright Chronicles, Volume 4, Number 2 (2026)

Author

Melina Murgel

Abstract

The Fulbright Project for the Modernization of Undergraduate Education (PMG) aims to improve engineering education in Brazil. As a teaching assistant to the project, I visited Harvard, Columbia and MIT to learn about innovative teaching strategies in these universities. I found that such innovation demands institutional incentive and support, which are fostered by teaching-learning centers dedicated to assist professors to redesign their teaching practices.

Keywords

Innovation in teaching • Teaching-learning centers • Pedagogical redesign • Undergraduate education • Active learning

Teachers often want to improve the way they teach and incorporate active learning in their classes. However, as willing as they may be to do so, they frequently do not have enough time to study and plan how to do that. Therefore, it would be beneficial for them to have specialized support, or specifically, someone who helps teachers to modernize their classes – a pedagogical redesign professional.

The design of reproducible teaching methodologies is one of the objectives of the Project for the Modernization of Undergraduate Education (PMG). The program is a partnership between Fulbright and the Brazilian government with the goal of improving undergraduate education in Brazilian universities, starting with engineering courses. The University of São Paulo is participating in the PMG through the Polytechnic School (Poli) chemical engineering course. As a post-doc at the University of São Paulo, I participated in the PMG and was awarded a grant to visit universities in the United States and learn about innovative teaching methods used there, with the intent to reproduce them at Poli.

People are often surprised to find out that I am a chemical engineer holding a PhD in science education. However, for me, these two things are not as opposite as they may seem; on the contrary, they are complementary. My goal has never been to work in a factory; I’ve always wanted to be a scientist and a teacher. The PMG was perfect for me. Since undergraduate school, I have been interested in active learning methods, and, early in my studies on this topic, I realized that putting these teaching strategies into practice could be challenging for many reasons. Therefore, I was very excited to see the teaching-learning methods used in leading universities.

During my academic mission, I had the pleasure to visit Professor Paulo Blikstein at Columbia University and Professor Eric Mazur at Harvard University. Once I was in Boston, I did not miss the chance to also visit the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). What an opportunity!

Professor Blikstein works with pedagogical redesign teachers. The first time I read about this concept I was fascinated by the idea of professionals who help teachers incorporate active learning in their classes. Moreover, Professor Mazur is widely known in science education for creating Peer Instruction, an active learning method in which students learn by sharing their knowledge with their peers. One of the strengths of this method is that it was designed for classes with many students; a reality at Poli and a challenge for most active learning methods.

Observing Peer Instruction and other active learning methods in practice was amazing. Additionally, I learned that innovation in teaching requires substantial institutional incentive and support. Columbia, Harvard and MIT provide incentive by rewarding excellence in teaching. To support professors to redesign their classes, Harvard and MIT have their own pedagogical redesign professionals working in teaching-learning centers, which seem to be the key for innovation in teaching. In this article, I aim to answer: What is a teaching-learning center? What does it do? And why should every university have one?

Columbia University

Based at the Teachers College – Columbia’s Graduate School of Education – I had the opportunity to sit with Professor Paulo Blikstein, who discussed the challenges for the modernization of education. He explained that improving teaching goes beyond the strategies and methods teachers use in their classrooms, and highlighted the importance of infrastructure and faculty mindset. According to Professor Blikstein, teachers are frequently willing to improve their classes, but often too overloaded and/or insecure to do it alone. In these cases, a little help from pedagogical redesign professionals may be very handy. However, as Blikstein pointed out, institutionalization of innovation is more difficult than innovation itself.

Further, according to Blikstein, large classes can hinder innovation if assigned to a single teacher; therefore, teaching assistants (TAs) are necessary as they can share the workload. In addition to human resources, appropriate physical space, equipment, materials, and time are required. Changes in curricular arrangement are also needed because it is necessary to synthesize “old” content to make room for current technology and market’s demands.

While offering institutional support to teachers is crucial, it is not enough. They also need incentives to change their mindset about teaching and their teaching strategies. And that, Blikstein told me, is the tricky part. Universities praise their faculty for doing research. Productive researchers receive more funding and get promoted. It seems like teaching is in their way. Rather than being something that professors are rewarded for doing well, teaching good classes is time-consuming and leads to little or no recognition. This is perhaps the most urgent structural change needed.

But how to do that? Teachers College started to seriously value teaching in the evaluation of faculty career progress. Faculty members are assessed by the students (as in many universities), but they also attend each other’s classes twice a semester and fill out an assessment form. With these results, innovative teaching methods can be identified and acknowledged. The recognition can take the form of career progress, prizes, bonuses, funding (e.g. for classes infrastructure, or attending congresses on education), visibility of initiatives, etc.

After my conversation with Blikstein about the relevance of infrastructure and faculty mindset, I understood that I should not focus on teaching-learning methods alone, but mainly the institutional support and incentive that enable them. This helped me to ‘resignify’ and drive my efforts in my academic mission.

Harvard University

At Harvard, I was pleased to observe several classes of Applied Physics 50 (AP50), conducted by Professor Eric Mazur. AP50 is different from any other class I have ever attended – I felt as if I were experiencing the so called “21st century education”. The course is project-based and has no lectures nor exams. The students are divided in cohorts that rotate between three sections: the check-in sections, the skills section, and the maker space sections. In the check-in sections, students acquire theoretical concepts needed for the project. They discuss, in small groups, solutions to tutorials and challenges that they have previously solved at home – this dynamic is based on Peer Instruction. When they decide they are ready, they ask a TA to check-in their solution. In the skills sections, they put these concepts into practice by performing experiments and writing a report answering guiding questions, which are also checked-in by an instructor. In the maker space they build their projects. While I was there, students were working on the construction of Rube Goldberg machines to learn about kinematics.

By observing AP50 taught by Professor Mazur, I concluded that the 21st century teacher might not be just a lecturer, but also a manager. Just like peer instruction, the strategies used in AP50 evolved across the years and have continually improved. It is notable that AP50 as currently taught demands an enormous infrastructure, and this is not feasible in every university – that is why the Mazur group does not provide a “recipe” for their success. However, they do publish many works on the theoretical basis of how and why it works – and research has shown that students learn more with peer instruction than with traditional teaching.

The success of AP50 demonstrates the potential of active learning. However, planning and conducting classes in which students are more active is not a simple task. Guided by my conversation with Professor Blikstein, I was not after teaching methods alone, but what makes them possible. That was how I found the Learning Incubator (LInc), a teaching-learning center that has a team of pedagogical redesign professionals to support faculty to redesign their courses, implement changes, and assess outcomes. When a professor is committed to redesign their course, they are exempted from teaching it, and an instructor is hired, so the professor can dedicate time to planning. Graduate students can also participate in the redesign, which contributes to their training as future teachers.

At the Learning Incubator, I met Salma Abu Ayyash, who is a Preceptor in Education Innovation. She told me that the creation of the teaching-learning center was a top-down decision, showing institutional incentive and support for innovation in teaching. It was important because, as it is hard to change the way one teaches, their biggest challenge is cultural. Salma’s advice was to find a few professors who are willing to improve and start with small changes. They will spread the ideas, and bring more people on board.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Due to their proximity, Harvard and MIT scholars frequently collaborate. Professor Peter Dourmashkin, from the MIT, also redesigned his Physics course to make it more active learning oriented, and exchanged ideas with Professor Mazur. Dourmashkin took part in the creation of Technology-Enabled Active Learning (TEAL), which was also designed for large classes, and uses Mazur’s Peer Instruction.

The in-person classes are part of learning sequences, and teachers count on six to nine TAs per section, who are an essential part of the course, like in AP50. Before classes, students access video-lessons and working problems in an online environment, MITx. In the classroom, they discuss the course content in further detail and work on problems in groups. After classes, students solve practice problems with checkable answers, and if they struggle with homework, they can go to office hours.

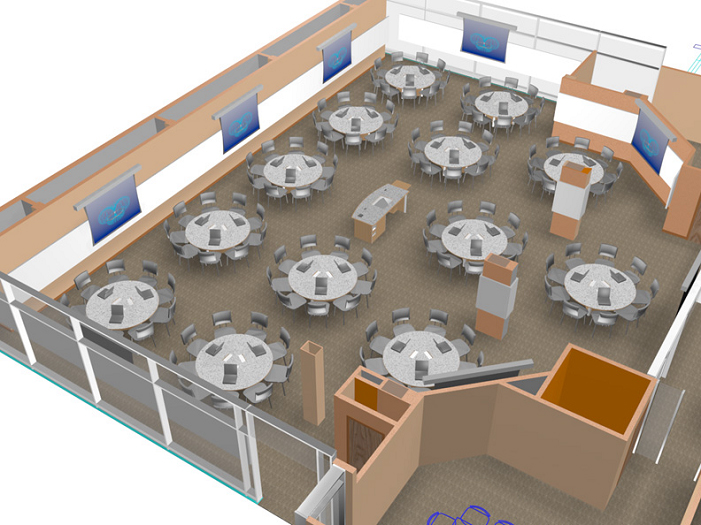

The TEAL classroom was created to foster active learning (Figure 1). It has 13 round tables with nine seats each and electrical outlets for group – accommodating around 100 students. All the walls have whiteboards with cameras pointed at them. Screens around the room project presentation slides and broadcast what the teacher is writing, allowing all students to see from their seats.

In my conversation with Dourmashkin, the importance of cultural change for innovation in teaching came up once again. He highlighted that TEAL is supported by three pillars: student culture, faculty culture, and administrative culture. At MIT I also met Professor Lori Breslow, who accompanied TEAL’s first steps and implementation. She expounded on how TEAL has a big digital component, but most importantly, a political component. When TEAL classes first began, some students and faculty members were against it.

According to Breslow, Professors Judy Dori and John Belcher played a significant role in this context. In a study, they showed that, compared to the traditional teaching previously used in the course, TEAL increased conceptual understanding and decreased course failure. In addition, students reported being positively impacted by the introduction of technology. Although complaints were heard, research results gave TEAL institutional support to keep going.

Although active learning cannot cover as much content as lectures, it can provide more depth and understanding. That is why many other active learning initiatives were born at MIT after TEAL. However, even at MIT, keeping students engaged remained a challenge. In order to help faculty members who want to modernize their classes, MIT also has a teaching-learning center, the Teaching + Learning Lab (TLL). Just like the Learning Incubator, TLL is a service center that makes innovation in teaching scalable. They are also responsible for TA training – preparing the next generation.

At the TLL, I met Lourdes Alemán, who is an Associate Director for Teaching and Learning. Once again, I was alerted that implementation of change is the hardest part. She pointed out that, for implementing change at an institutional level, it is important to address professors’ concerns and offer what they need. Alemán explained some strategies that have worked in TLL.

Small groups with regular meetings guided by facilitators allow building a community of individuals who cooperate and help each other. These groups have senior and new hires. Alemán mentioned that it is important to select senior professors who are in consonance to the culture and practices that the institution wants to perpetuate. In the groups’ meetings, they share their success cases and exchange ideas. Faculties need to feel that the meetings are useful, and be rewarded for the time spent there. TLL also incentivizes professors to visit each other’s classes, creating a feedback loop in which they learn with each other. Disseminating positive results is important because, according to Alemán, examples of people from the same institution are more convincing than data coming from different contexts. Therefore, her main advice was to arm ourselves with data – that is what scientists listen to.

Lessons learned

When I boarded to the US, I knew that this academic mission would be a life-changing adventure. I brought back home many valuable lessons. On a personal level, this whole experience taught me that support is one of the most important factors for career success. As a STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) educator, I learnt the name of something that I had been draw to since my graduate studies: pedagogical redesign. And, as a PMG assistant, I found out that the key for the modernization of undergraduate education is institutional support and incentives.

Innovation in teaching is not something that teachers should be expected to do alone.

Innovation in teaching is not something that teachers should be expected to do alone. Institutions must provide support – which can be done through the teaching-learning centers – and incentives – by rewarding professors for good classes in their career progress. The teaching-learning centers allow scaling up innovation in teaching, so rather than being teacher-related, it becomes part of the institution’s culture.

The institutionalization of an innovative teaching culture starts with small changes and the creation of a community. It requires bringing together people who are ready and willing to change how they teach, and assisting them to redesign their classes. It is also important to collect data, measure outcomes, recognize their efforts, and reward their results. Moreover, it is necessary to provide appropriate infrastructure; mainly through the investment in teaching assistants, as it not only helps current faculty with their classes, but also contributes to the training of the next generation of professors.

To make it all happen, the teaching-learning centers at Harvard and MIT count on education experts who have knowledge about the content – in this case, the engineering domain. After all, it seems like my background in engineering and my PhD in science education are not unrelated! Now, I embrace the mission to bring the teaching-learning centers as an innovative solution to Brazilian universities.

Further Reading

- Crouch, C. H., and Mazur, E. (2001). Peer instruction: Ten years of experience and results. American Journal of Physics 69(9), 970-977. https://doi.org/10.1119/1.1374249

- Dori, Y. J., and Belcher, J. (2005). How does technology-enabled active learning affect undergraduate students’ understanding of electromagnetism concepts? Journal of the Learning Sciences, 14(2), 243-279. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1402_3

- Hochgreb-Haegele, T., Fernandez, C., and Blikstein, P. (2022). Addressing challenges in changing science teaching in the Global South: An integrative model for science education reform in Brazil. Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of the Learning Sciences-ICLS 2022, 1433-1436. https://repository.isls.org/handle/1/8506.

Biography

Melina Murgel is a postdoctoral researcher in Science Education at University of São Paulo, Brazil. She was awarded a CAPES-Fulbright grant to visit the U.S. in 2024 as part of the Project for the Modernization of Undergraduate Education (PMG). During this period, she was hosted by P. Blikstein and E. Mazur and had the opportunity to engage in enlightening conversations with L. Breslow, P. Dourmashkin, L. Alemán, and S.A. Ayyash. She is deeply grateful to her supervisors, C. Fernandez and A. Tonso, and to everyone who contributed to making this experience possible. You can contact her at melmurgel@usp.br.