Fulbright Chronicles, Volume 1, Number 2 (2022)

Author

Jonathan Hollander

Abstract

During Fulbright tenures in India (1992) and Malaysia (2011), collaborations led to the creation of choreography, bilateral exchanges and the launching of an arts council. The Fulbright awards served as catalysts for the flourishing of relationships that have continued to grow and produce outcomes in the art, social and educational spheres. The “foreign” became “familiar”, the acts of giving and receiving became intermixed, and personal and professional growth were nurtured in unexpected ways.

Keywords

India • Malaysia • dance • collaboration • choreography

Magical Keys

I think of Fulbright awards as keys to the world, and not just any keys. Fulbright keys have magical powers. With them I opened doors to relationships, collaborations, interactions, learnings and creative productions that have continued to proliferate and blossom over the past 30 years.

I think of Fulbright awards as keys to the world, and not just any keys. Fulbright keys have magical powers. With them I opened doors to relationships, collaborations, interactions, learnings and creative productions that have continued to proliferate and blossom over the past 30 years. And yet it was all so totally unexpected. Back in 1991, I was into the 15th year of my life as a choreographer and artistic director of Battery Dance in New York. My work was being performed in the New York City area and on tour in various parts of the U.S. However, my creative and intellectual interactions were almost entirely with other Americans based in New York City. Although I was hoping to expand my horizons internationally, I had no idea how to do so.

That is until my friend and colleague Janaki Patrik, the brilliant American-born Kathak dancer and a Fulbrighter herself, encouraged me to apply for a Fulbright, saying, “they’re looking for artists.” Up until that point, I had thought of Fulbright as a prestigious award given exclusively to academicians with blue-ribbon credentials as scholars, writers and thinkers with lots of letters after their names. How could I, a dance artist, college drop-out, presume to be qualified for such an honor?

When my appointment for a 3-month position in India actually came through – attaching me to the National Centre for Performing Arts in Mumbai and Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, with side engagements at two of India’s leading dance institutions and a 4-city tour of the State of Andhra Pradesh, I was beyond elated. As a choreographer, I was supercharged by what I imagined lay ahead: the opportunity to meet peers, senior artists and students in the rich world of Indian dance. India’s dance culture is beyond compare, and I hoped there would be fertile ground for sharing in the post-Colonial period of the early 1990’s. But no research nor preparation could have allowed me to predict the many ways in which I would be able to give and receive during the Fulbright experience.

Surprises in Ahmedabad – Dance and Design

During my stay in Ahmedabad, in between teaching master classes and organizing my own company’s performances, there was ample time to watch rehearsals and performances by the great Indian classical dancers based there and to compare notes about our lives as artists. Amidst all of the hectic activity, I fell into an unexpected and quite remarkable opportunity. The National Institute of Design (NID) was nearing the end of term and graduation of its Masters of Fine Arts students in the textile and garment design program. Instead of a runway model show, the visionary head of the department asked me if I would choreograph dances to showcase the graduates’ collections.

Always hungry to take on new challenges, I jumped at the chance to upend the usual model of costumes being designed FOR dance, and this time design dances FOR the costumes. I didn’t need to be paid since my stipend from Fulbright covered my living expenses and NID offered one of their guest houses on campus. My only condition was that I wanted to work with trained dancers and this resulted in the bringing together of two leading arts and educational institutions – Darpana Academy of the Arts, with its prestige as an incubator for great dance, and NID itself. Though located on the same road, they had failed to collaborate for a decade or more due to some long-forgotten tiff. The designer whose work stood out, and whose collections became the focus of my choreographic interventions, was Sandhya Raman. That was in 1992. As of today, Sandhya is the leading costume designer for dance in all of India and even among the Indian diaspora in the U.S. and Europe. For me, a small work entitled “Moonbeam” was inspired by Sandhya’s gossamer thin white starched cotton Mughal robes with geometric window-pane pattern of interwoven gold threads. Famed Indian dancer Mallika Sarabhai and her then dance partner Sasidharan Nair were the couple for whom I created this duet and it had a life back home in the U.S. and on tour to Turkey, Azerbaijan, and many other U.S. and foreign cities when successive pairs of dancers learned it years later. A true mélange of Indian and American influences born of my Fulbright experience, a dance piece that served as a metaphor for the entire experience.

The Arts and Social Impact in Malaysia

Nearly 20 years later, in 2011, having been selected for the Fulbright Specialist roster, new doors opened for me in Malaysia, a country I had visited with Battery Dance six years earlier. Creative thinking on the part of Nicholas Papp, the American Cultural Affairs Officer at the U.S. Embassy Kuala Lumpur, allowed for a solution to the many requests we were fielding from our Malaysian hosts at Akademi Seni Budaya Dan Warisan Kebangsaan (ASWARA) and Sutra Dance Theatre. I didn’t see how I could achieve successful outcomes on my own until Nick proposed combining my Fulbright award with an Embassy grant, enabling my two-part Specialist program to gain from the presence of two of my senior teaching artists from New York in Part I; and by the entire Battery Dance Company in Part II. (Specialist programs allow for projects to span more than one visit as mine did.) What transpired was memorable, served as a model for future programs with refugee integration and adaptation, and has been sustained through on-going relationships with students with whom we worked and who have now come into their own as leading professionals in the field of dance internationally.

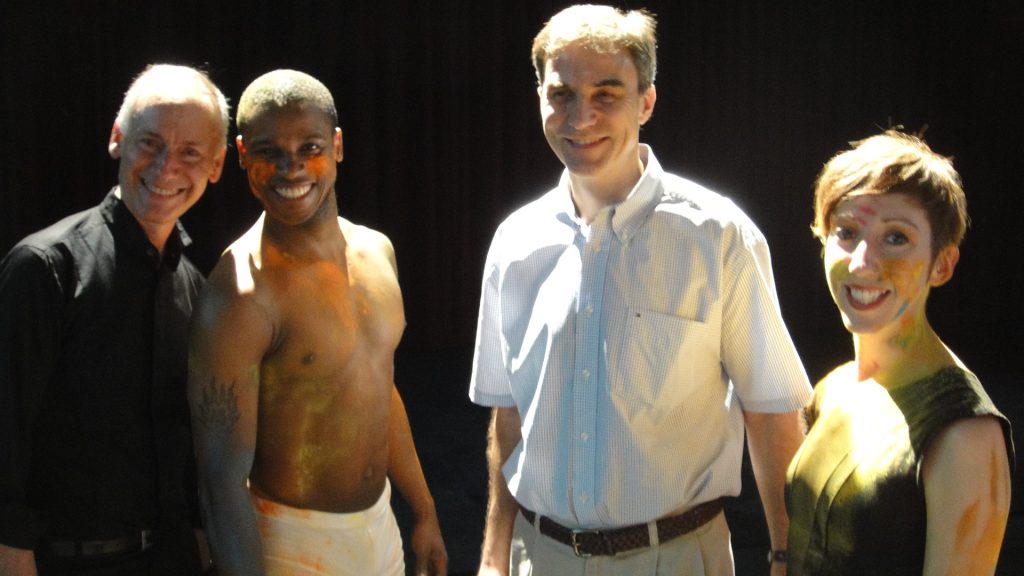

In Part I of the assignment, Sean Scantlebury, Robin Cantrell and I conducted workshops with 50 dance majors at ASWARA, the leading dance conservatory program in Kuala Lumpur and ranked among the top in the region. We utilized the methodology that had become Battery Dance’s signature arts education project at home and abroad: Dancing to Connect. In this 20-hour intensive workshop series, participants are given the tools to choreograph their own dance, breaking the imitative mold so frequently utilized by American dance companies when they go abroad (including, I should admit, Battery Dance in prior times).

The students proved to be so creative and motivated that at the end of a week of training, we had two large and compelling pieces of choreography. We combined these works with two duets by Robin and Sean, and a few traditional Malay, Chinese and Indian dance items by the ASWARA dancers and voila. As a result, we had an evening-length program that was performed before a packed audience including U.S. Ambassador Paul Jones and his family and Malaysian dignitaries.

The underpinnings were set up to allow for a truly impactful integration of the high level ASWARA students with much younger United Nations High Commission Refugees from Myanmar and Sri Lanka. Having experienced and excelled in the creative modality of Dancing to Connect, a group of hand-picked students from ASWARA shadowed and partnered with our dancers in working with the refugee youth, encouraging them to explore physicality and expression through dance. This was a radical experience for the participants who had been living in tight quarters with their families in the refugee camps outside of KL with little opportunity to move freely, to participate in joyful experimentation and to socialize with Malaysians.

Phase II of my Fulbright Specialist assignment coupled with the Embassy grant took place 6 months later and allowed the relationships with ASWARA students to develop even further. As our 5 dancer/teaching artists fanned out to different parts of Malaysia (Penang, Kota Kinabalu, Kuang), each was accompanied by an ASWARA graduate, who not only teamed up in the pedagogical activities but also performed solo or in a duet with their Battery Dance trainer. Putting my Fulbright lens to work, examining and evaluating all of this activity, what I see is a merging, melding, shedding of any concept of “the other”, and instead the breeding of a deep trust, curiosity and enrichment across what had started out to be very different nations, religions, backgrounds and life and career expectations.

In yet another aspect of the collaboration, Ramli Ibrahim, Malaysia’s most celebrated dancer and founder of Sutra Dance Theatre, and I created choreography for each other’s dancers and the two companies presented four joint performances at the leading arts center in KL, one of which was a private show for the local Fulbright Association and others invited by the Embassy.

Bilateral Exchanges and Changing Attitudes

Successful international exchange programs like the Fulbright are meant to be catalysts for ongoing interactions and engagements, a kind of starter fluid. My Fulbright experiences in India and Malaysia have gone way beyond any notion of U.S. cultural imports. I have a ready-made opportunity to present international dancers in New York through the Battery Dance Festival each summer, where relationships built during my Fulbright overseas experiences yielded performances by Indian and Malaysian dancers for the enjoyment of American audiences.

In 1993, the year after my Fulbright in India, I organized cross-country U.S. tours by two of India’s most illustrious dance companies that had never been seen by American audiences. It was a reckless endeavor by a neophyte presenter and took all the passion, stamina and grit I could muster. I remember bucking what would now be considered unacceptably racist attitudes on the part of mainstream media in cities as large as Houston and LA, where I heard statements like, “We don’t cover ethnic dance. Our critics can’t write about forms with which they are unfamiliar and the audiences those performances attract don’t read our papers anyway.” Nevertheless, high visibility presenters such as Lincoln Center (New York City), Annenberg Center (Philadelphia), and colleges and universities across the country showcased these dazzling companies and audiences responded in kind.

I followed up by organizing two more tours by Indian dance companies before realizing that the effort was causing personal and institutional burn-out. I approached the Indian Consul General in New York, Harsh Bhasin, and asked him to consider inviting the diasporic community to attend a panel discussion by non-profit arts experts that might lead to the creation of an Indian Arts Council. He agreed and the idea took hold. The Indo-American Arts Council (IAAC) was launched with Ms. Aroon Shivadasani as its founding director and over the next 20 years, Aroon built a host of annual programs including film, theater, music, literary arts, visual arts and dance festivals. I stayed on the Board to support Aroon and served for the entire duration of her tenure.

Battery Dance and IAAC teamed up each year in presenting the Erasing Borders Festival of Indian Dance and literally dozens of India’s best dancers have appeared on our stage each August, with generous reviews and photos adorning the New York Times, Financial Times, TimeOut NY and The New Yorker. Gone were those bad old days when critics ignored Indian dance.

Drumbeats, Songs and Poetry

The year after my Fulbright, I felt it was time to dig into Indian music and to see whether my aesthetic and the talents of my dancers could find an authentic response. I contacted the late Bengali-American tabla player Badal Roy, and we improvised in the studio in the hot summer weeks in New York. Badal sat on the studio floor, playing drum rhythms and speaking in metered patterns called the “bols” and I experimented with movement evocations. I summoned up memories of my Fulbright time in Ahmedabad, where the Sabarmati River wound its way beyond the embankment on which Natarani Amphitheater perched. Donkeys traversed the riverbed that was dried up except for a small rivulet towards the middle where washerwomen beat saris against stones after dunking them in the reddish water.

Badal’s beats and my vivid memories served as rich springboards for what became, “Seen by a River”, choreography that toured India in 1994. While on tour, we had dinner in the home of Badal’s friends in Kolkata and were treated to a recital by the host’s daughter. The performance of what turned out to be songs by Nobel Poet Laureate Rabindranath Tagore inspired my Songs of Tagore, performed across Europe, U.S., Sri Lanka and India during the 50th Anniversary of Indian Independence in 1997. I turned to Sandhya Raman once again who created the eye-catching costumes and to Indo-American painter Anil Revri to create the sets. I left one space in the choreography to be filled by an Indian classical dancer for which Mallika Sarabhai initially took up the part. Kolkata native musicians Samir and Sanghamitra Chatterjee, who had moved to Queens, NY, just in time to serve as consultants, were critical to the development of the production and accompanied us at Asia Society in New York, and on tour.

Fresh from the 17-city Indian tour of Songs of Tagore, I decided to collaborate with a Chennai-based producer on PURUSH: Expressions of Man, a production designed to highlight outstanding male dancers across the genres of Indian classical dance whose gifts were being overlooked. Historically, Indian dance was the purview of male dancers who even portrayed female parts in drag, but current audiences much preferred female dancers. We created a medley of performances by 10 male dancers and musicians; and I contributed Testimony of the Nataraj, a duet for contemporary dancers, Kevin Predmore and John Freeman, with an original musical score by Badal Roy and the jazz guitarist Ken Wessel. The premiere performances took place at Lincoln Center in New York and Music Academy in Chennai, before a triumphant cross-country U.S. tour.

Unexpected Outcomes on Stage and Cyberspace

Following the extensive interactions with Malaysian dancers at ASWARA, two of our program participants achieved MFA degrees at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts and one, Md. Fairul Zahid, was selected to present his choreography at the Battery Dance Festival in 2016. As the first Malaysian to receive a faculty appointment at the LaSalle College of the Arts in Singapore, Fairul will bring a team of dancers to the Battery Dance Festival in August, 2022

During the pandemic, Battery Dance pivoted to the virtual world, recording over 1,000 classes, performances and discussions on topics related to dance and cultural diplomacy. This platform brought attention to many talented dance-makers from India and Malaysia with performances, interviews and classes broadcast on Battery Dance TV to audiences across 206 countries with 1.5 million digital views.

The magical Fulbright keys continue to open new doors, as Bethany Mitchell, the next generation of Battery Dance Fulbrighters, carried out a vibrant Fulbright Specialist program in Mazatlán, Mexico in the Spring of 2022.

Notes

- For information on Battery Dance, visit www.batterydance.org

- Profile in DNA – Mumbai https://bit.ly/3jWI60y

- Documentary Film Trailer “Moving Stories” — https://bit.ly/389uPiE (Complete film is available on Amazon Prime and Vimeo on Demand)

Biography

Jonathan Hollander was a Fulbright Scholar to India (1992) and Fulbright Specialist to Malaysia (2011). He founded Battery Dance in 1976 and has choreographed over 70 works presented in 70 countries. He has established arts education residencies in New York City public schools and created the Battery Dance Festival, NYC’s longest-running public dance festival. His awards include the Federal Cross of Merit from the President of Germany and Choreography Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. He has been a keynote speaker for the U.S. Department of State, Aspen Institute, Foreign Policy Association and The Selma Jeanne Cohen Lecture on Dance for the Fulbright Association in 2018. He can be reached at jonathan@batterydance.org