Fulbright Chronicles, Volume 2, Number 1 (2023)

Author

Dom Caristi

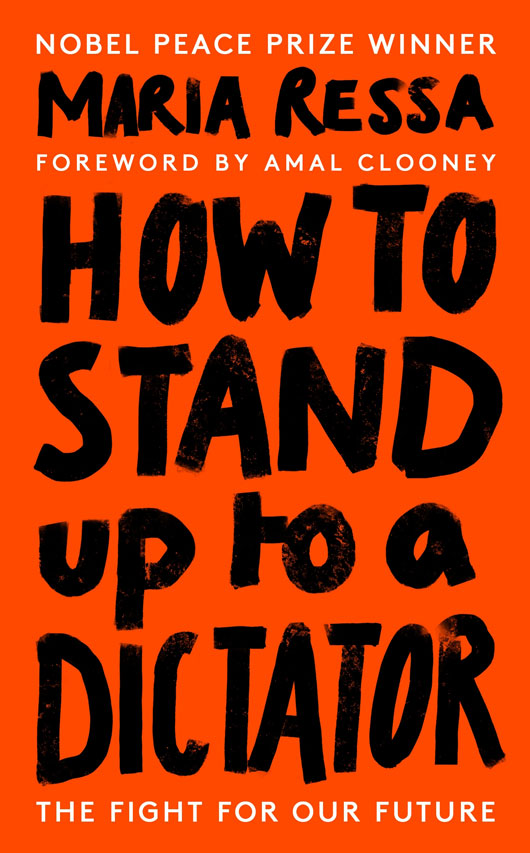

How to Stand up to a Dictator by Maria Ressa, a US student Fulbrighter to the University of the Philippines in 1986.

Maria Ressa is the latest in a long line of Nobel Peace Prize Laureates to publish a book providing advice to the world. Ressa’s book is part memoir and part call-to-action as she tells the story of her life, how she came to be involved in Philippine media, and her long, tedious, and expensive battle fighting multiple lawsuits brought against her by the Philippine government in an effort to silence her. In January she was acquitted on four counts of tax evasion but as of this writing is still fighting other suits, including a cyber libel conviction.

Ressa is not the first to be critical of social media platforms, but she provides extensive evidence to support her assertion that “the very platforms that deliver the news we need are biased against facts” (4). Democracy is threatened, especially in emerging countries, but as we have seen, the problems they experience soon become the problems of established democracies. Her harshest criticisms are aimed at Facebook. Over the years she met with multiple officials—including Mark Zuckerberg—and provided them with facts and figures describing the damage they were causing, but her pleas went unanswered. Facebook’s most frequent response was to do nothing. When they did act, their actions were often counterproductive.

The book is divided into three parts, the first of which covers her first forty years. Born in the Philippines, her mother brought her to the US at age ten. She learned very early the lessons that would carry her through the difficult years ahead: make the choice to learn, embrace fear, and stand up to bullies. This section includes her Fulbright year when she returned to the Philippines and found her calling in journalism. She tells of her years working as a journalist for state-owned media, the news division of a Philippine entertainment conglomerate, and even CNN. In those years she developed her sense of duty to the truth. While some journalists seek balance in their reporting, Ressa considers truth more important. She says good journalists “would not give equal time and space to known climate deniers and climate change scientists” (72).

The second part of the book focuses more on technology: the impact of the internet and Ressa’s founding of Rappler, a Philippine online, news-gathering company that relies heavily on audience engagement. The goal from the beginning was to encourage “participatory journalism” using crowdsourced content. She had been encouraged by the activism she saw that resulted in real challenges to dictators (such as the Arab Spring). It wasn’t long before she found that the same technological advances could be turned against people just as easily, “fueling the rise of digital authoritarians, the death of facts, and the insidious mass manipulation we live with today” (105). It didn’t help that Facebook’s algorithms distributed false information faster and more broadly than the truth. “Facebook represents one of the gravest threats to democracies around the world,” she wrote, “and I am amazed that we have allowed our freedoms to be taken away by technology companies’ greed for growth and revenues” (137). Spreading anger and hate is more profitable and fuels the “us versus them” mindset.

The final section of the book focuses on the attacks that both Ressa and Rappler have endured over the past fifteen years and includes a call to action. In perhaps the greatest irony of all, she notes, “Free speech is being used to stifle free speech” (185). Intimidation, character assassinations and even threats are used to silence dissenters. Thanks to social media, threats get amplified and repeated far beyond the original post.

Ressa calls on everyone to become involved. It’s not just a fight for the future of news; it’s a battle for democracy.

Throughout the book, Ressa emphasizes two important defenses against the deception, hate, and fascism from the powerful: journalism and civic engagement. Journalism has been attacked and we can see the effects. Media are characterized as enemies and liars which despots use to their advantage. If people lose trust in the media, their reporting on the lies, illegal actions and even murders by the people in power will be ignored. At the same time news media have lost money to social media, providing them with fewer resources to fight back. A weakened mass media plays into the hands of oppressors.

The second defense is civic engagement, and Ressa calls on everyone to become involved. It’s not just a fight for the future of news; it’s a battle for democracy. She wants us to demand accountability from technology; protect and grow investigative journalism; and build larger communities of action.

A lot has changed in just a few decades. The internet has made new communication channels possible that can have tremendous impact. How to Stand Up to a Dictator is a powerful book that reminds us of the dangers of allowing the power of government officials and the new power of social media platforms to operate unchecked.

Maria Ressa, How to Stand Up to a Dictator. New York, NY: HarperCollins. 2022. 301 pages $29.99.

Biography

Dom Caristi is Professor Emeritus of Media at Ball State University. He was a Fulbright Scholar to Slovenia in 1995 and Greece in 2009. He served as the Fulbright Program Adviser at Ball State and for six years was a Fulbright Alumni Ambassador, visiting 40 campuses to encourage other faculty to apply for a Fulbright. He currently serves on the Board of Directors of the Indiana Chapter of the Fulbright Association. He is co-author of the textbook, Communication Law: Practical Applications in the Digital Age, now in its third edition. His email is dgcaristi@bsu.ed