Fulbright Chronicles, Volume 2, Number 1 (2023)

Author

Mark Tardi

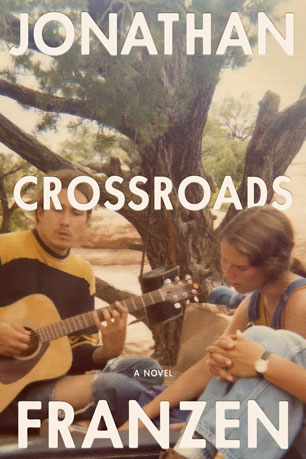

Crossroads by Jonathan Franzen, Fulbright Scholar to Germany in 1981.

At this stage in his illustrious career, which now includes six bestselling novels and numerous collections of nonfiction, Jonathan Franzen can do pretty much whatever he feels like. Resting on his laurels, however, is clearly not on his itinerary. Crossroads, his ambitious sixth novel (and the opening salvo in a planned trilogy), is set in a fictional early 1970s suburb of Chicago called New Prospect, and there we meet the Hildebrandt family, all of whom are on the cusp of something.

There’s Russ, an associate pastor at a comfortable suburban church in the midst of a midlife crisis; Marion, Russ’s supportive wife––“a mother of four with a twenty-year-old’s heart” (270); and the children: Clem, Becky, Perry, and Judson. Clem is the oldest and the unabashed atheist in his family––“Science and delusion had no common ground” (574)––initially a student at the University of Illinois until withdrawing to accept his Vietnam draft number in pursuit of social justice. Becky is the beautiful, popular girl at school à la any number of John Hughes’s films, plotting her future, and her younger brother Perry is the hyper-intelligent outsider with a penchant for recreational drug use, transactional friendships, and the flexible logic of a natural schemer. Judson, the youngest of the family and in primary school, appears to be a sweet little boy (but we only catch glimpses of him through others). The Hildebrandt teenagers, however, burn with their own youthful self-certainty and solipsism: the certainty in the righteousness of their convictions and intelligence (though in differing ways), and the often rigid certainty in their assessment of their parents’ failings.

The title, Crossroads, serves as both thematic and emotional compass for the novel: the eponymous youth group at First Reformed Church, an organization that figures prominently in the lives of the three oldest Hildebrandt children and the catalyst for what Russ refers to as his “humiliation.” Humiliation for Russ, however, is complex and spiritually clarifying: “The sense of rightness at the bottom of his worst days, the feeling of homecoming in his humiliations, was how he knew God existed” (12). The action that unfolds in the novel explores various socio-historical crossroads in American history: 1960s counterculture giving way to the “ME” Decade; the looming failure of the Vietnam War; the growing recognition of pluralistic and multiple “Americas”; the crossroads between the vibrancy and hope of youth and the pains of maturity; the intersections of various forms of spirituality, and the costs of economic, racial, and social progress in different communities; and, finally, the unintended intersections of mistakes that braid a family together. As all of the Hildebrandts will learn (sometimes despite their best efforts), none of their decisions or desires exists in a vacuum.

Franzen is perhaps at his best when he’s offering unvarnished portraits of his characters’ deeply human motivations, yet some of the novel’s most gracious insights come from his consideration of faith: for Russ, “Prayer was an inflection of the soul in God’s direction” (325–26); for Becky, in a marijuana-induced epiphany, “Time can’t be measured without light” (266). At the same time, the Hildebrandts are like fractals and the closer they’re examined, the more the details proliferate––often heartbreakingly so (in the interest of avoiding spoilers, Marion’s early life in California or where Perry’s effort to be a better person take him are but two examples.)

Readers of earlier books such as Freedom or The Corrections will recognize Franzen’s fluency with the American Midwest, and there are numerous passages skillfully describing Illinois environs; as a native Chicagoan, a description such as “the ground-level haze that industrial agriculture seemed to generate in winter, a smog part dampness and part nitrates” (94) certainly left me nodding in silent agreement. What’s more, although much of the action unfolds just before Christmas 1971, like Nathaniel Hawthorne or Mark Twain, Franzen leverages an historical period to zoom in and out of the lives of his characters in order to make poignant observations about our contemporary moment. Put simply, there’s a timely quality to the novel as it connects current hot-button issues––such as the potentially cringe-worthy behaviors or beliefs of earlier generations, the pitfalls of groupthink and cancel culture, questions of (in)authenticity or cultural appropriation, and the spiritual void––to suggest these dynamics very much predate the present and have, in fact, long been a part of the American experiment. For example, despite decades of genuine social activism and community involvement, devoting time and resources to marginalized and oppressed groups, in a moment of introspection, Russ recognizes that to those in the Crossroads youth group, he appears to be little more than “the fantasy of a dork freeloading on another man’s charisma” (229)––in this case, the more charismatic Rick Ambrose, the younger, assistant pastor and Russ’s nemesis. Becky’s observation that “almost everything in life was vanity” (548) could easily be filtered through Instagram.

Crossroads is a gripping portrait of an American family at the tenuous intersection of aspiration and disintegration.

With elements of the picaresque––much of the action takes place in the fictional Chicago, but extended flashbacks and the propulsive plot take us to California, Arizona, New Orleans, Europe and even Peru––Crossroads is never static; it’s a gripping portrait of an American family at the tenuous intersection of aspiration and disintegration, and I’m excited to see what roads the next two volumes in Franzen’s project will take.

Jonathan Franzen, Crossroads. New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux. 2021. 592 pages. $30.

Biography

Mark Tardi, a Fulbright Scholar to Poland in 2008-09, is a recipient of a 2022 NEA Fellowship in Literary Translation, a 2023 PEN/Heim Translation Grant, and the author of three books, most recently, The Circus of Trust (Dalkey Archive, 2017). Recent work and translations can be found in The Experiment Will Not Be Bound (Unbound Edition, 2022), Full Stop, LIT, Interim, Denver Quarterly, The Millions, Circumference, and elsewhere. His translations of The Squatters’ Gift by Robert Rybicki (Dalkey Archive) and Faith in Strangers by Katarzyna Szaulińska (Toad Press/Veliz Books) were published in 2021. He is on the faculty at the University of Łódź. His email is mark.tardi@gmail.com