Fulbright Chronicles, Volume 2, Number 1 (2023)

Author

Logan Puck

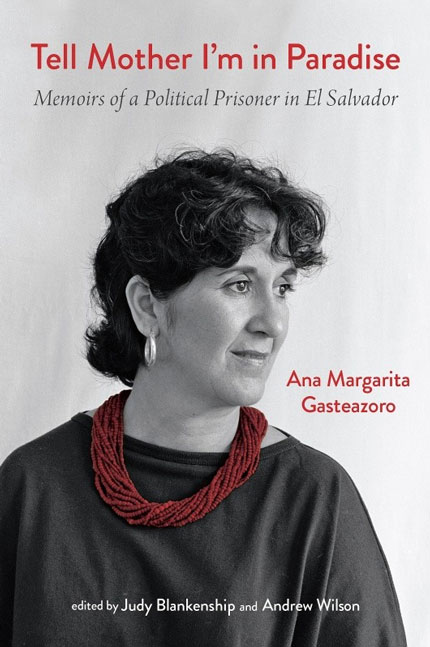

Ana Margarita Gasteazoro, Tell Mother I’m in Paradise: Memoirs of a Political Prisoner in El Salvador, edited by Judy Blankenship and Andrew Wilson. Judy Blankenship was a Fulbright Scholar to Ecuador in 2000, 2005, and 2013-14.

Tell Mother I’m in Paradise: Memoirs of a Political Prisoner in El Salvador is an exciting read that provides a unique perspective on Salvadoran politics and society before and during the Civil War. It is an excellent book for those interested in Salvadoran history, revolutionary struggle, and gender and class politics.

A riveting portrait of a determined woman who turned against her privileged, conservative upbringing to struggle against injustice.

In 1986, Judy Blankenship and Andrew Wilson, two NGO workers, met Ana Margarita Gasteazoro and became fascinated by her life story. From that moment on, until Gasteazoro’s death from cancer in January of 1993, Blankenship and Wilson visited her a number of times to record her story. Although they completed the first manuscript in the 1990s, Gasteazoro’s family did not approve publication of the book until decades later. The delay provides the reader with the feeling of listening to a voice unearthed from the past. Blankenship and Wilson have masterfully edited the recordings into a riveting portrait of a determined woman who turned against her privileged, conservative upbringing to struggle against injustice.

Gasteazoro begins her narrative by describing her wealthy Catholic upbringing in San Salvador where she lived with her parents, four siblings, and a plethora of servants. As a teenager, Gasteazoro’s rebellious spirit created constant tension between her and her parents, especially her mother. This theme runs throughout the book. Fed up with her antics, Gasteazoro’s parents eventually sent her to a religious, all-girls school in Guatemala where she befriended a nun and a young social worker who exposed her to the widespread poverty in Guatemala City. This is the moment we see the first seeds of Gasteazoro’s revolutionary consciousness emerge, though it would take another decade before she made good on the lessons she encountered in Guatemala City’s slums.

Part Two of the book focuses on Gasteazoro’s transition to political activism. The Salvadoran military’s constant meddling in politics and increasing use of terror and brutality led Gasteazoro to become an active member of the social democratic National Revolutionary Movement (MNR) where her education, knowledge of foreign languages, and worldliness served as a major asset for the cause. As her resolve against the regime hardened, she eventually became a secret operative supporting the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), the guerrilla organization waging war against the Salvadoran government.

Curiously, Gasteazoro rarely dwells on major events in Salvadoran history. For example, she only devotes a few paragraphs to the murder of Archbishop Óscar Romero and provides little reflection on her experiences being fired on by government troops at Romero’s funeral procession. Gasteazoro does, however, go into great detail describing her time at party meetings and international leftist conferences and offers colorful accounts of the activists and revolutionaries she meets at these events.

Gasteazoro’s narrative also reveals the challenges of the moment, for instance, the near-constant sexism within Salvadoran society and the leftist movement itself. Gasteazoro grapples with unwanted sexual advances and dismissive attitudes from fellow male activists. As Gasteazoro states, “Men don’t like women being more intelligent than they are” (121). She also contends with disdain for her upper-class roots, as some militants derisively called her bourgeois and questioned her commitment to the cause.

The final and most fascinating section of the book focuses on Gasteazoro’s imprisonment. Gasteazoro’s revolutionary activities led to her arrest and detention in a National Guard torture facility, which she describes in chilling detail. After ten days of beatings, sleep deprivation, and interrogations, she was transferred to a women’s prison where she immediately joined the Political Prisoners’ Committee of El Salvador (COPPES). No longer subjected to the male gaze, Gasteazoro flourished as she advocated for prisoners’ rights, organized her fellow inmates, and strove to create a strong community based on solidarity. “It was all very exciting for me,” she explains. “I had spent hours in the Guardia Nacional thinking about what I would do when I got to prison, and now I had these experienced, practical compañeras to work with. I felt wonderful: I had been there only two hours but I could see clearly the work ahead. I felt we were capable of organizing the whole damn prison” (155-156).

Gasteazoro brings the prison to life through vignettes about the women she encountered. The stories give these women a sense of humanity and highlight the complicated nature of relationships behind bars. They also shed light on how the challenges faced in the prison reflected the same problems facing the Salvadoran left at large and its efforts to overthrow the state. Instead of uniting, Gasteazoro explains how the political prisoners factionalized into the political parties and revolutionary movements that echoed their affiliations in the outside world. These groups competed with each other in their attempts to control the COPPES agenda and recruit new inmates to their side. She colorfully describes this intense competition for new recruits: “whenever a woman arrived in the section, each organization would try to pull her into their orbit. Sometimes the competition was about benefits: a better bed, or a more comfortable mattress, or nicer sandals. At times it became a scramble to get there first and to trip up the competition on the way. The new woman would be overwhelmed by all the attention” (188).

Tell Mother I’m in Paradise is an illuminating work that deserves to be placed alongside other classic memoirs by women, such as Rigoberta Menchú and Elvia Alvarado, who fought for social justice in deeply unequal and violent settings. It is a particularly good complement to The Country Under My Skin written by the Nicaraguan poet and novelist, Gioconda Belli. Belli’s memoir is a similar personal account of a Central American woman wrestling with her upper-class background as she engages in a revolutionary struggle in a heavily patriarchal setting. The poetic, dramatic flair of Belli’s work is nicely balanced by Gasteazoro’s more grounded narrative. It almost feels as if you are sitting in the room with Gasteazoro as she tells the story of her life.

Ana Margarita Gasteazoro Tell Mother I’m in Paradise: Memoirs of a Political Prisoner in El Salvador. Judy Blankenship and Andrew Wilson, eds. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 2022. 250 pages, $34.95.

Biography

Logan Puck is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Political Science at George Washington University. His research focuses on crime, violence, and security in Latin America with an emphasis on plural policing in Mexico. He earned an M.A. in Latin American Studies from the University of California, Berkeley, and a PhD in Politics from the University of California, Santa Cruz. He was a Fulbright-García Robles Scholar at the Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas (CIDE) in Mexico City from 2013 to 2014. His email is logan.hj.puck@gmail.com