Fulbright Chronicles, Volume 2, Number 2 (2023)

Author

Steven Darian

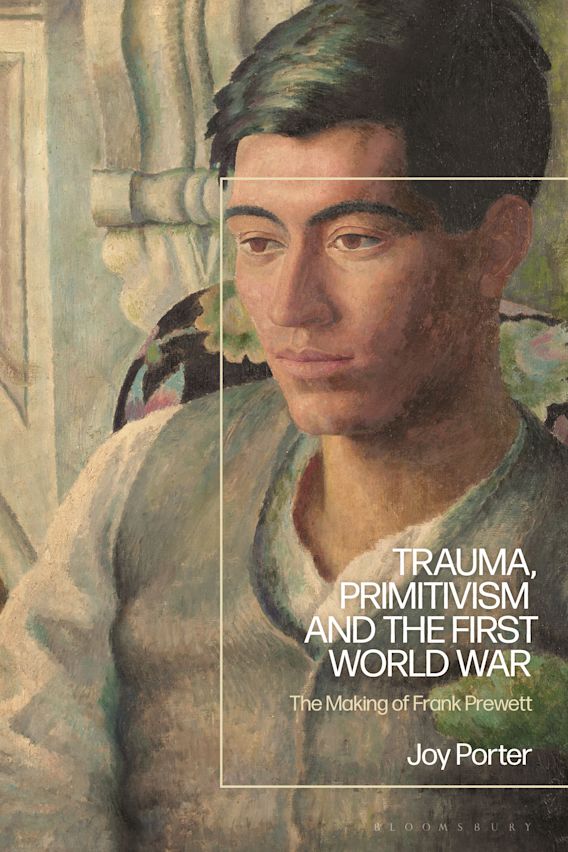

Trauma, Primitivism, and the First World War: The Making of Frank Prewett by Joy Porter, a Visiting Fulbright Scholar from the UK to Dartmouth College, 2015

This book follows the life journey of the Canadian World War I poet Frank Prewett and the life-changing effects of that war on him and his generation. It was also a time of incredible change in almost everything: in politics; in physics and psychology; in business and industry; in social relationships; and in literature. The author, Joy Porter, a professor of Indigenous history at the University of Hull (UK) is brilliant in weaving together the incredibly complex interactions that encompass the events of World War I, that began before the war and follow on from it.

The trauma of war led him to adopt a second persona, a new identity––that of an American Indian.

The book lays bare the reactions to the war, of people in general, and of writers of the times, especially the poets. These include those who observed it from afar, and those who fought in the trenches. This included Prewett, who experienced some of the worst fighting of the war (at the Somme and at Ypres), and was seriously injured. So much so that the trauma led him to adopt a second persona, a new identity––that of an American Indian, adding Indian colors to his clothing, alluding here and there to his Indigenous heritage, and adding “Toronto” to his name. (The Canadian’s city’s name is derived from a Mohawk word.)

Prewett spent time recovering from his war wounds at a hospital in southern England, not far from Garsington Manor in Oxfordshire which attracted some of the early twentieth century’s most significant and most influential literary figures, such as E.M. Forster, Walter de la Mare, and T.S. Eliot. And it was there that Prewett began to form an attachment to the literary set. Evidently he made a great impression on many of his fellow writers, some of whom (Virginia Woolf and Robert Graves) predicted greatness for him.

What made Prewett’s poetry unique, according to the author, was the poet’s focus on the iron will needed to withstand the brutalities of war, and the horrors that never left you, but remained, hovering in the shadows, waiting to leap out at the slightest provocation. Ultimately, he looked upon war as ageless in a world “alienated from the rhythms of nature” (45) and bereft of tradition.

As for his poems, apart from the love poetry that tends to be traditional, there are the lugubrious lyrics of war. Here is an excerpt from his “Mad Tom Beuly:”

Say boys, I saw my brother,

Which one ought to, you see

In a proud and well-connected

and loving family.

The rats had chewed his flesh for food,

He shows a bony knee,

But the smile upon visage

Is a cheering sight to see (158).

The condition Prewett had fallen prey to is called Primitivism, which we could define as a longing for an earlier, supposedly simpler world, where benevolent nature played a major part. It was a state of mind whose cause, in retrospect, could be viewed pathologically or culturally. In other words, it was induced by trauma or as a reaction to the times since it also expressed itself in other ways: among painters of the period, most notably, Van Gogh and Gauguin. It harkened back to a golden age that never was.

Some were convinced that the new flood of knowledge sweeping the world “heralded potential disaster” (200). The poet Yeats emphasized the Second Coming in his poem by that name: “Things fall apart; the center cannot hold.” Spengler’s canonical Decline of the West predicted not just the end of German supremacy, but the whole of Western Civilization, including the United States. Such reactions engendered what Porter calls “protest memory” (199), remembering things that were not quite true—and especially in the case of many writers, never intended to be true. Alternative realities. Prewett himself “decided to tell dominant groups a story they wanted to hear” (197).

Porter cites examples from earlier and more recent times of Indigenous people amusing themselves in this way: of the Caribs in the West Indies telling Columbus of the gold and many-headed cannibals that existed just over the horizon. Or “the young Samoans who told Margaret Mead they were sexually promiscuous, as her 1960s reading public wanted to be themselves” (197). Memory, as your reviewer has often reflected, is at best, an act of imagination.

The tremors of WW I, as portrayed in this book, will ripple over time, and will continue on through many moons: the concepts of empires and nationhood; of colonialism and identity; attitudes towards race and gender; and the relationship between memory and reality. Prewett continued to be praised by the war poets and, according to the author, is still considered one of Canada’s finest poets.

Joy Porter. Trauma, Primitivism, and the First World War: The Making of Frank Prewett. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2022. 289 pages. $115.80 hc, $39.75 pb.

Biography

Steven Darian has a PhD from NYU in Applied Linguistics and is professor emeritus from Rutgers University. He’s taught at Penn and Columbia and lived, taught, and studied in many countries, three of them on Fulbrights (India, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan). He has more than 10 years experience as editorial director for a small publishing house in NYC and has written over a dozen books, ranging from Understanding the Language of Science, to The Heretic’s Book of Death & Laughter: The Role of Religion in Just About Everything (2022). He can be reached at darger27@yahoo.com