Fulbright Chronicles, Volume 2, Number 2 (2023)

Author

Chloë G. K. Atkins

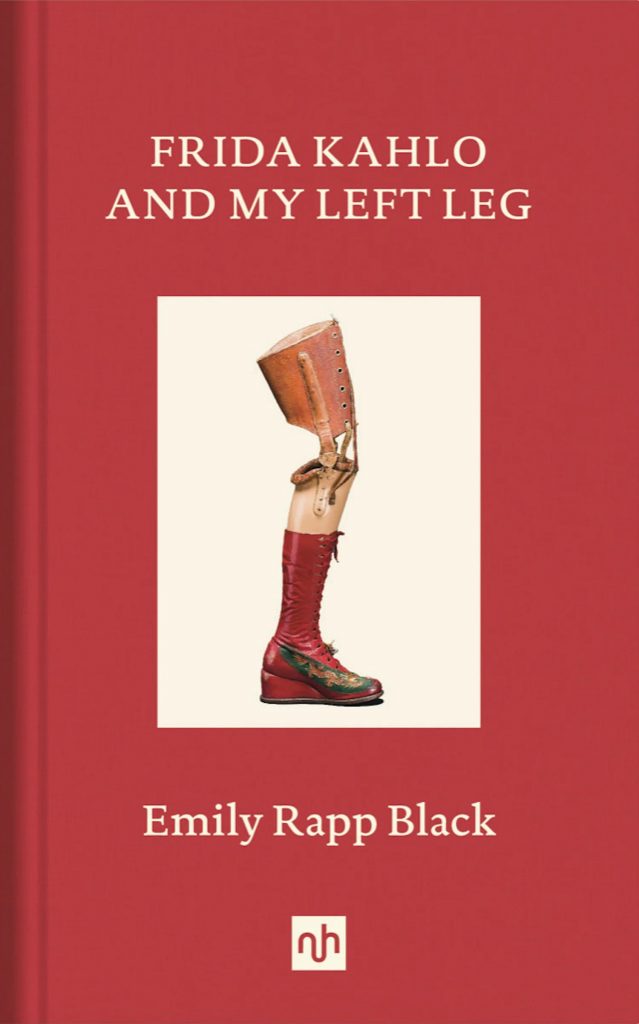

Frida Kahlo and My Left Leg, by Emily Rapp Black, who was a Fulbright Scholar to Seoul, Korea, in 1996.

Frida Kahlo includes monkeys in many of her self-portraits. In one of them, she depicts the face of a small black monkey as well as her own—two visages: one simian, the other human, stare intently out of the frame. Emily Rapp Black’s latest memoir, Frida Kahlo and My Left Leg, mimics this duality. Black, a New York Times bestselling author, ponders Kahlo’s disabled life, work, and posthumous exhibits, as she reflects on her own experience of amputation and loss. (Kahlo contracted polio as a child and then was further badly injured in a bus accident as a young woman.) Black creates a collage of observations, memories, and reveries. She muses about Kahlo’s paintings and disability experiences, interpenetrating them with that of her own consciousness of “exceptional bodies.” Black became an amputee at age four, and her first child, Ronan, died of Tay Sachs disease at the age of three. The book meditates on threads of loss and resurgence as they weave themselves throughout the narrative of Kahlo’s iconography and Black’s own life experiences.

In reflecting about Kahlo, the author focuses on the medical paraphernalia which accompany the artist, and which also continue to simultaneously intrude and facilitate her own life. She writes, “I began my toddler life in a metal brace secured to the body by Velcro straps and a foam bump under the left foot that made my legs even, or ‘line up’ as we said, ‘Is it lined up? Do you feel lined up?” (103).

Black ponders Kahlo’s disabled life, work, and posthumous exhibits, as she reflects on her own experience of amputation and loss.

As she walks through the Kahlo Museum in Mexico City, Black feels the skin of her stump uncomfortably sweating and abrading against the sleeve of her artificial leg. At various interludes in the book, she recalls quasi-sexual encounters with prosthetists who sculpted her limbs over the years as she stood or hopped in her underwear through their workshops waiting for them to re-work casts or prototypes. Recent technology means that she has more than one prosthetic leg: one for running, one for high heels and another for everyday use. Black relies on these innovations to function, yet she writes, “Each night the body is reshaped with the removal of the prosthetic, placed next to the bed within easy reach, and each morning refashioned through the act of reattachment. Each day this rebirth” (32). Kahlo also captures this oscillation between separateness and wholeness when the painter transforms her plaster corsets, orthotic shoes, and metal braces into art. She covers the various accoutrements with images, in some way taming their foreignness but also highlighting them as objects to be manipulated by her creativity. Both women need, resent, rely on, and transform their assistive devices. The pieces of equipment are icons and tools, remaining external yet integral to both Kahlo and Black.

Because society judges women by their appearance, physical disability and/or disfigurement create particular psychic and social burdens for women. Black opines:

[A] woman is embodied, and she is judged accordingly. We want to think that we are beyond this, that we are more than our bodies, but, in the end, we are not. We are both easily reduced to the sum of our parts, but sometimes we are reduced only to our parts. As a woman who wears a permanent machine, I still feel this acutely. (110)

The admixture of femininity and disability is a difficult one. Kahlo navigates it through her visual art which also becomes a part of her presentation of self—there is a distinctive Frida style. Similarly, Black and her amputee girlfriends dress to accommodate their sometimes noisy, badly colored prosthetic limbs: “I select outfits even for the most casual event with great calculation: what to hide, what to reveal, a cautious consideration of how much attention and of what variety I am willing to withstand or absorb or explain or contextualize” (15).

Kahlo can sometimes be seen as a pathetic vamp, clinging to her lover/husband, the famous painter Diego Rivera, because she is desperate and disabled. Similarly, people objectify Black, staring at her in public. There are even men who are attracted to the seeming vulnerability of female amputees and who fetishize and harass the young woman. But both Kahlo and Black are not weak; instead they seek “immense joy in living” (8). Pain is a part of their lives but not the centrality of their existences.

Kahlo’s plural miscarriages and Black’s son Ronan’s premature death from Tay Sachs haunt the book. As women who experience the chronicity of pain, maternity circulates through their lives. Ronan’s short life occurs within the descent and destruction of the writer’s first marriage. Her mothering is careful yet delimited. Ronan dies because his parents’ genes betray him. The fault in some way lies with them, but he suffers the mortal penalty: “Everything was wrong with my son, and yet he was perfect and singular. He was my creation, but I would never, as Dr Frankenstein had, leave him. My love for him remains a burden I will never put down” (112).

Kahlo loses three children by either abortion or miscarriage –the consequences of her broken and endlessly, medically repaired body. Despite technologic interventions, none of these young lives can be saved, but their mothers endure and even thrive. Kahlo continues to create until her final moments on the planet. Black births and mothers another child—and writes this wonderful book.

Both women are testaments to the capacity, as Black tells us, of human beings to be “born through moments of rupture, again and again…” (30).

Emily Rapp Black, Frida Kahlo and My Left Leg. London: Notting Hill Editions, 158 pages. $19.35. 2021

Biography

Chloë G. K. Atkins has a PhD in Political Theory from the University of Toronto and a postdoc in law from Cornell University where she was a Fulbright Scholar in 1999. Her prize-winning book, My Imaginary Illness (Cornel Univ. Press), came out in 2010, and she writes about disability, bioethics, health equity, vulnerable identities, human rights, and phenomenological and narrative scholarship. She is the primary investigator of “The PROUD Project” on Under-Employment and Disability, funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada; the Department of National Defense Research Council of Canada; TechNation, Catherine & Frederik Eaton Family Foundation; the University of Toronto Global Teaching Grant; and private donors. Besides her Fulbright award, she has held Killam, Clarke, and SSHRC fellowships. She can be reached at chloegk.atkins@utoronto.ca