Fulbright Chronicles, Volume 2, Number 4 (2024)

Author

Shepard Forman

Abstract

Serendipity and opportunism enabled this unmoored young man to acquire a Fulbright-Hays fellowship in Brazil from 1961-62. The fellowship was marked by a clash of wills between my insistence on “learning by living” and the Fulbright Commissioner’s strict interpretations of the contractual nature of my Fulbright proposal. The intervention of a renowned anthropology professor opened a path to a professional and personal life that I believe would make the Fulbright Commission proud.

Keywords

Brazil • social justice • history • Amazon • anthropology

Prelude to a Fulbright and My Encounter with Brazil

I imagine most Fulbrighters exclaim that their Fulbright experience had a profound effect on their lives. The same is certainly true for me, although my Fulbright story precedes my fellowship year in Brazil (1961-1962), extends long past it and was written in large part by my defiance of the rules and regulations the Brazilian Fulbright Commission sought to impose on me. Both professionally and personally, it has led to a lifetime engagement with Brazil and to a rewarding career as a university professor, a human rights and social justice activist, and a proponent of international cooperation in economic and post-conflict peace and development.

The story begins in my junior year at Brandeis University when I was first introduced to the Portuguese-speaking world. While researching a book on Portuguese Africa, Professor James Duffy asked a group of us in his Spanish lit class to help him with some comparative research on other areas of Portuguese colonialism. I literally drew the short straw and set off to learn what I could about the Southeast Asian half-island of East Timor, best known for a Magellan stop-over and its marginal contribution to the spice trade. I found scant information on the island itself but struck a vein of interest in the malfeasance of colonialism and the rights of subjugated peoples that would guide my career in the years ahead.

Bachelor’s degree in hand, I set off for New York to discover what life had in store for me. My application for a training program at the hemispheric shipping giant, Grace & Co., rejected – despite my proficiency in Spanish – “because we only hire prestige graduates here”, I refocused my sights on Madison Avenue and landed a job writing blurbs on weekly programs for TV Guide magazine. In search of something more enriching, I enrolled in evening courses at NYU in Spanish and Italian romance literature, driven perhaps by a vague notion that an advanced degree in literature might steer me toward a career in literary publishing. It led me instead to the Fulbright program.

To pay tuition and cover my boarding house rent in Greenwich Village, I took a day job as functions manager at NYU’s Loeb Student Center where I largely managed room assignments and set-ups for diverse university events. It was 1960, I was one year out of college and still figuring out life at 22, when Title VI of the Language and Area Studies Program was introduced at NYU. I recall a meeting with Celeste Coutinho, the administrator of NYU’s new Brazil Studies Center, who urged me to switch from Italian to Portuguese. I did so motivated by my earlier exposure to Portuguese colonialism and the promise that I could give up my day job, study full time, receive a fellowship that outpaced my NYU salary and enjoy more of Greenwich Village delights during my now freed-up evening hours.

I enrolled in a reading course in early Portuguese love poems and another on orthographic changes from Spanish to Portuguese, which were fun but concentrated my mind on late medieval language more aligned to vulgar Latin than to modern day Portuguese, not exactly what the National Defense Education Act had in mind. One of my readings, led me to an epic poem about Isaac de Castro, an expelled Portuguese Jew who studied with Spinosa in Holland and, at around age 20, went to Recife, then part of Dutch holdings in the Brazilian Northeast. For reasons unknown, he crossed over into Portuguese territory, was arrested in Bahia, shipped back to Lisbon for trial by inquisition and burnt at the stake after refusing to abjure his faith. Something drew me to Isaac de Castro and, upon discovering that the entire inquisition transcript was intact at the National Library in Lisbon, I proposed a translation of the trial record and an interpretation of the text for my master’s degree essay; a proposal rejected as neither history nor literature.

Increasingly interested in Portuguese colonial history, I switched my NDEA fellowship to the area studies program, refocused my thesis research on the role of the Jew in Dutch Brasil and signed on to a course on Brazilian society and culture with the renowned Columbia University anthropologist Charles Wagley, who was filling out the fledgling curriculum at NYU’s Brazil Center. Dora Vasconcelos, the poetess Consul General of Brazil in New York, became the patroness of our class, invited us to consular events, an exhibition match with the Bangu soccer club, and the jaw-dropping annual Carnival Ball at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel. Brazil became my passion, and I jumped when Celeste Coutinho urged me to apply to the recently inaugurated Fulbright-Hays Fellowship program in Brazil, advising me to choose a topic with more contemporary relevance. A short-lived 1930s workers strike in São Paulo had caught my eye in a history course and became my topic of the moment.

My application was accepted with the caveat that I bolster my spoken Portuguese with a three-month intensive language training program at the University of Rio Grande do Sul where, in the summer of 1961, I was placed with a Portuguese only speaking family and their two teen sons who were raising a baby jaguar that took pleasure in leaping on me from atop the refrigerator and a living room bookshelf. I spent a lot of time away from the house, learning enough street Portuguese to augment my fellowship at the horse races and be cited for “most progress in language learning” among my cohort at our certificate ceremony. The best of my learning occurred in clubs and coffee shops with Brazilian friends who awakened me to the importance of contemporary politics. At that time, Janio Quadros renounced his presidency in August 1961 after just seven months in office, succeeded by his populist vice-president João Goulart. The military began to manifest its custodial intention, and I became more attuned to the politics and culture of a country in flux.

A mixture of excitement and apprehension accompanied me to Rio de Janeiro in September 1961 for the month-long orientation to my Fulbright fellowship. Despite the removal of the capital to the newly inaugurated Brasilia, Rio was still the cultural and intellectual hub of the country. I became intoxicated with the sights, sounds and tastes of Rio, frequenting the popular dance clubs of ZiCartola and Estudantina, an Afro-Brazilian Umbanda terreiro and the Mangueira samba school. I certainly spent too much time on the iconic Copacabana beach. I had come armed with introductions to the family and friends of a young Brazilian journalist, Leona Shluger, who Celeste Coutinho had encouraged me to meet on the eve of my departure from New York. Leona anticipated the energy, spirit, and promise I encountered in this ready-made community and through her I learned much about the aspirations, hopes, and ambitions of young Brazilians. Leona and I would marry seven years later, and together we would build a life devoted to public service now in its 57th year.

Rules, Regulations and Brazilian Dexterity

To fulfill my fellowship obligations, I dutifully attended classes at the Federal University of Brazil and the Commission’s orientation events. It came as somewhat of a shock, then, when the Fulbright Commissioner, Fernando Tude de Souza, reminded me that, “by contract”, I was to take up my Fulbright in the archives of São Paulo where I had proposed to study the 1930s labor strike. I argued strenuously that a more open-ended learning experience in a rapidly changing Brazil would be perfectly consonant with the intention of the Fulbright-Hays program, but to no avail. Not even the ministrations of the simpática program administrator, Patricia Bildner, could convince Tude de Souza of the wisdom of rewriting my “contract.” I reluctantly left for São Paulo where, after a dismal week in a dusty basement archive, I unilaterally decided that a paper on the labor strike would neither fulfill my obligation to US taxpayers or to my own sense of purpose. I returned to Rio, rented a room in a classic art deco apartment building a block from Copacabana Beach, and settled in for a year of learning by living.

In one of my frequent meetings with fellow Fulbrighters, Diana Siedhoff, a linguist who as Diana Natalicio would become the 30-year President of the University of Texas at El Paso, observed that Rio was not representative of Brazil and suggested that as a group we explore the countryside. I immediately signed on, and the two of us set off for Pirapora, Minas Gerais, boarding a San Francisco paddlewheel river boat heading north through the backlands toward Paulo Afonso falls, soon to become one of Brazil’s major hydroelectric sites. The boat got stuck on a sandbar for five days, I caught malaria and Diana had me taken ashore at the pilgrimage town of Bom Jesus de Lapa where she correctly assumed there would be a pharmacy, saw to my transfer to a hospital in the state capital of Bahia and oversaw my recovery. We then travelled north to Manaus on the Amazon River where Diana decided to return to her classroom studies and I, now interested in rural poverty and development, determined to travel the Amazon if I was truly to know Brazil.

I spent the next two months “hitchhiking” on my exchange student visa by boat and plane down the Amazon. At that time, students could travel free with the Brazilian air force (FAB), and I managed passage on a plane I believed to be going to Iquitos, Peru, from where I could ferry back across the river to Brazil. To my astonishment, we landed in Quito, Ecuador, for which I had no entry document and where I was detained by immigration authorities. Fortunately, there were Ecuadorian students on board, returning from an exchange program in São Paulo. Mario Zambrano, son of a lawyer and brother of a soccer star, negotiated my “parole” in the care of the Zambrano family, but at the cost of surrendering my passport which I was promised would be returned to me in a week’s time at the southern border crossing between Guayaquil, Equador and Tumbes, Peru.

With new horizons ahead of me, I continued south by bus and on truck bed, mostly in the company of patient and kindly indigenous Peruvians and Bolivians, often with chickens and llamas and once with a pet cayman, stopping in Lima and La Paz and villages enroute. This journey included crossing Lake Titicaca on a traditional straw raft and spending a week in Santa Cruz, Bolivia at the home for orphaned and abandoned children founded by the missionaries John and Elena Stansberry before catching the Maria Fumaça (smoking Maria), wood-fired train back to São Paulo, intrigued by the stunning differences in Latin American societies and cultures and satisfied that I had more than met the requirements for a successful Fulbright learning experience.

“Not so,” declared Tude de Souza, who called me a “vagabond and bum,” said I had abrogated my Fulbright contract, that my fellowship was being rescinded and that I should return to the States, just 3 months into my year-long stay. Depressed, I withdrew to a bar in Copacabana hoping that a beer or two would help me formulate an undeniable defense. Unexpectedly, Charles Wagley, the Columbia professor who had introduced me to Brazil at NYU, entered the bar. What was I doing there at noon on a sunny Rio day, he asked. I restrained from redirecting the question but told him of my plight. Chuck laughed, said he and his wife Cecilia were going to the Northeast for a semester of travel and research while finishing his book, Introduction to Brazil. He said they could use a research assistant and asked if I would join them — if he were able to convince Tude de Souza to stay my execution.

Tude de Souza relented, providing I enroll in an anthropology class at the University of Bahia with the dean of Brazilian anthropology, Thales de Azevedo. I spent the next six months in Salvador, where I rented a room above the gatehouse of a Swiss cacao exporter and his wife, providentially situated across the road from the terreiro of Mãe Menininha, the renowned mother of the saints at the most venerated condomblé in Bahia, where I deepened my appreciation of Afro-Brazilian culture. Mostly, I traveled through the backlands with the Wagleys in their Rural Wyllis. Dr.Thales never took attendance for Tude de Souza and too modestly assured me I would learn more anthropology on the road with the Wagleys than I would in his classroom.

I spent much of my time in the company of Socorro Ferraz and Fernando Barbosa, students at the Federal University of Pernbambuco and their fellow organizers of Francisco Julião’s Peasant Leagues. At one meeting in the rural town of Surubim, hundreds of peasants gathered to receive medical attention (Fernando) and attend literacy classes (Socorro) while a law student instructed the peasants on their rights to land and to fair wages. The local priest called his parishioners, including young boys in the parochial school, to a counter demonstration. Landowners’ hired gunmen arrived to break up the meeting and in the confusion that followed, a twelve-year old boy was shot and killed. In what I later learned was a pre-arranged plan, I was hustled away to a safe house while the priest exhorted the crowd to find that Cuban (me) and hold him accountable. I was hidden away until near dawn when I was secreted back to Recife and the Wagley’s comforting hands.

The Fulbright Effect

Those six “Fulbright” months were probably the most formative of my career. Brazil was in political and social flux marked by spontaneous worker strikes in every sector of the economy, disrupting daily life. Banks would close, schools cancelled classes, buses didn’t run. A Carnaval song summed it up: “Rio de Janeiro, the city that seduces; by day there is no water; at night there is no light”! The collapse of public services and the failure of state and federal government to address public needs gave rise to the political populism, urban and rural social movements and guerilla activity that would roil the country throughout my Fulbright year. Three years later, on April 1, 1964, I watched the warships enter the bay at Copacabana while doing dissertation research in Brazil and questioned the value of my academic work as the country plunged into 21 years of dictatorial darkness. Arbitrary arrests and disappearances followed. Friends and colleagues – including the Peasant League organizers mentioned above – were dismissed from their jobs and fled into exile.

A dozen years of university teaching convinced me I was more suited to a life of activism; I gave up tenure and returned to Brazil as advisor on higher education and rural development in the Ford Foundation’s Rio office, a life-changing career move clearly influenced by my Fulbright experience.

I recorded the impressions of that year in an article, “Up from the Parrot’s Perch,” in a book appropriately entitled Young Americans Abroad. I later published an article about the events in Surubim in, Cadernos Brasileiros V (1963), a Brazilian journal of social and political commentary. At Wagley’s invitation, I went on to do a PhD in Anthropology at Columbia University. I was drawn back to the stark landscapes of the Brazilian Northeast for my dissertation fieldwork and subsequent research on the political and economic engagement of peasants in Brazilian national life. A dozen years of university teaching convinced me I was more suited to a life of activism; I gave up tenure and returned to Brazil as advisor on higher education and rural development in the Ford Foundation’s Rio office, a life-changing career move clearly influenced by my Fulbright experience. I was honored to serve, at President Clinton’s invitation, on the National Humanities Center Steering Committee on the Future of the Fulbright Exchange Program on its fiftieth anniversary.

Notes

- Duffy, James, Portuguese Africa, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass. 1959.

- Forman, Shepard, The Raft Fisherman: Tradition and Change in the Brazilian Peasant Economy, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana 1970; The Brazilian Peasantry, Columbia University Press, New York, New York 1975; translated as Camponeses: Sua Participação no Brasil, Editora Paz e Terra, Rio de Janeiro,, 2007; “Up from the Parrot’s Perch” in Young Americans Abroad, Roger H. Klein and Jospeh S. Lelyveld, eds., Harper & Row, 1963.

- Wagley, Charles, Introduction to Brazil, Columbia University Press, New York, New York 1963.

- Upon retiring from the UN, Leona Forman founded BrazilFoundation, a US and Brazilian NGO providing financial support for community-based social projects throughout Brazil www.brazilfoundation.org

- Fulbright at Fifty, a report of the Steering Committee on the Future of the Fulbright Educational Exchange Program, Then National Humanities Center, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, 1996.

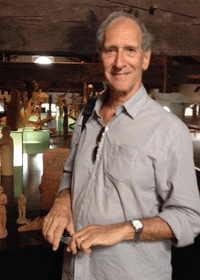

Biography

Shepard Forman (PhD anthropology, Columbia University; post-doctoral fellowship, Economic Development, the Institute of Development Studies in Sussex, England) taught political and economic anthropology and Latin American Studies at the universities of Indiana, Chicago and Michigan and the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro; conducted field research in Northeast Brazil and among the Makassae peoples of East Timor; directed programs in Human Rights and Social Justice, Governance and Public Policy, and International Affairs at the Ford Foundation; and founded the Center on International Cooperation at New York University to develop more effective multilateral responses to global problems, including peacekeeping and post-conflict reconstruction and development. He authored and edited nine books and published multiple articles on anthropology and international public policy. Shep is married to Leona Shluger Forman, a Brazilian journalist, former director in the UN’s Public Information department, and founder of the BrazilFoundation. They have two children: Alexandra Joy Forman, founder of the Instituto Urca in Rio de Janeiro, devoted to storytelling with a social purpose; and Jacob Forman, a film and TV writer who works closely with production companies in Brazil; and a Brazilian granddaughter, Lara Rosa Forman. He and Leona are permanent residents of Rio de Janeiro and spend summers and fall at their family farmhouse in Ashfield, Massachusetts. He can be reached at: shepardforman@gmail.com