Fulbright Chronicles, Volume 3, Number 1 (2024)

Author

Lekelia D. Jenkins

Abstract

As a Fulbright Scholar in Australia, I explored the Queensland’s fishing industry’s views on sustainability, especially the proposed use of video cameras to monitor fishing activity and catches. Using PhotoVoice, fishers took photos representing their concerns and discussed these images in a focus group. I collaborated with artists to transform these photos into impactful artworks. My Fulbright created new partnerships, opened a new geographic area for research, and highlighted the value of art for communication.

Keywords

fisheries • sustainability • PhotoVoice • science • art • electronic monitoring • onboard cameras

As a marine sustainability scientist, I grapple with troubling issues like endangered species survival, ocean degradation, and the livelihoods of those dependent on the seas. Seeking a more uplifting topic for my sabbatical, I focused on growing my secondary research area of environmental science art. Connecting with Australian scholar Adjunct Associate Professor Lisa Chandler led me to the University of the Sunshine Coast (USC), a marine environmental science art hub with experts like Chandler and Professor Claudia Baldwin who use art for marine and fisheries outreach. The Fulbright Scholar Award from the Regional Universities Network (RUN) of Australia facilitated collaboration with USC’s experts and Steve Eayrs, an Extension Officer with the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation (FRDC) who explore change management and cinematic documentaries for fisher safety.

The newly launched Fulbright RUN Award perfectly matched my background and interests. Geared to encourage scholars to work at rural universities like USC in Queensland, one of the award’s foci is “Crops and Foods for the Future.” This focus includes fisheries sciences, education, and extension, which align seamlessly with my expertise in sustainable fisheries and environmental science art for science education, extension, and social change. My collaborators and I developed my Fulbright project to explore the ways in which art can be used to communicate fisheries sustainability.

The Problem

Many Australians acknowledge that it is vital to have a fishing industry that can supply locally caught fresh seafood while at the same time having policies and practices that protect the marine environment and enable a safe and sustainable fishery. Sustainable seafood is essential to human health, especially for food security and as a source of protein and other nutrients. Governments recommend that people eat more fish, and demand is expected to increase in the coming decades. To meet this demand and human health needs, we need sustainable fisheries. Yet, the seafood supply is threatened. Overfishing, bycatch (i.e., the incidental capture of non-target species), and habitat destruction have significantly reduced global fish stocks.

Conventional methods to encourage sustainable fishing practices lack effectiveness. A recent Australian study revealed communication, education, and outreach shortcomings, with fishers often unaware of research outcomes. The study identified a strong link between fishers’ resistance to voluntary bycatch reduction and their lack of readiness for change and disinterest or apathy toward additional bycatch reduction efforts.

My Fulbright research in Australia focused on gauging the perspectives of Queensland’s commercial fishing industry on sustainability. Specifically, I explored fishers’ opinions on the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries’ (QDAF) initiative to use onboard cameras to monitor fishing activities and record interactions with protected species. Industry resistance stemmed from concerns about personal and data privacy, potential access to footage by third parties leading to negative media campaigns and worries about the compatibility of camera equipment with efficient and safe fishing operations.

The Project as Planned

Some fisheries professionals are exploring change theories to support the move toward sustainability, including the concept of change readiness, which involves the willingness and capacity to alter behavior. This readiness is based on cognitive (knowledge and beliefs) and affective (emotions, values, motivations, attitudes) elements. However, many extension efforts in areas like fisheries focus solely on transferring information to improve cognitive readiness for change. Theories of affective readiness suggests visual and auditory communication, such as art with pictures and music, can enhance affective readiness by evoking emotional responses and motivation.

Photovoice originated as a community development technique and is also a qualitative visual research method and art form. It offers a unique approach to enhancing affective readiness. In this process, individuals use photos or videos to depict and discuss their environment and experiences, aiming to catalyze change. The captioned photos can be shared with the public and policymakers, providing insights into the photographers’ lives. Photovoice involves individual and group reflection, making it suitable for emotion-laden issues to express values and interests. It fosters mutual understanding, offers rich insights into complex topics, emotionally engages participants and viewers, enhances local control and autonomy, and conveys local expertise to policymakers.

The project focused on the research question, “How can photovoice enhance fisheries sustainability education?” Fishing industry members captured photos reflecting their values and concerns, particularly regarding sustainability and onboard cameras. Subsequently, they participated in a focus group to discuss their photos and explore improved communication strategies for conveying industry values.

The Project in Practice

Despite extensive contingency planning in my Fulbright proposal, on-ground conditions required adaptability, patience, and trust-building. The Fulbright mandated a four-month duration, starting in January, which coincided with the fishing season, so fishers had little time to participate in the project. The controversies around onboard cameras and fishing sustainability intensified, especially with government fisheries ban announced during my Fulbright. Amid this tense environment, I dedicated the initial two months to relationship-building within the fishing industry, attending meetings, and engaging with industry leaders. This time-consuming but crucial step paved the way for partnerships with the Moreton Bay Seafood Industry Association and the Women in Seafood Association, facilitating participant recruitment for the study.

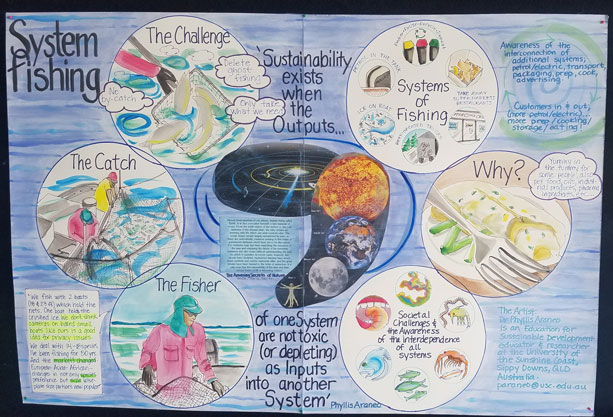

Despite a one-month delay awaiting ethics approval, I conducted a focused group with three participants in the final week of my Fulbright. Interest from other fishers was substantial, but fishing conditions limited participation. Recognizing the insufficient data for analysis, I adjusted the study’s focus to serve as a proof of concept for evolving the Photovoice method to create more impactful visuals. I recruited two artists, Associate Lecturer Phyllis Araneo and Associate Lecturer Lyris Snowden, faculty at USC. They partnered with two fishers to create artworks that further express the fishers’ ideas and the artists’ responses to them. This was a meaningful evolution of PhotoVoice because all the fishers said they were concerned that they did not have the skills to produce good photos. They also stated that onboard cameras were so controversial that it was risky for them to voice particular views for fear of repercussions from other fishers.

Impact of my Fulbright Project

This project aligns with the mission and 5-year plan of the FRDC, a key funder of fisheries research in Australia. As their 2020-2025 plan outlines, the FRDC focuses on capacity building, shaping culture, building relationships, and establishing shared principles and values. The plan aims to improve community trust, respect, and value through effective communication, including storytelling about seafood. Photovoice and this project are well-suited to contribute to this outcome by exploring how photos and narratives can serve as fisheries extension tools, telling compelling stories that foster affective readiness for change.

My Fulbright created new partnerships and opened a new geographic area for research. I am now on a trajectory to conduct more fisheries sustainability research in Australia. Notably, during my Fulbright, QDAF struggled to recruit participants for a field trial of various onboard camera systems because the fishing industry had continued concerns about data privacy and accessibility. After the conclusion of my Fulbright, Steve Eayrs and I proposed and successfully convinced QDAF to fund a workshop to reframe the issue of onboard cameras, reset discussions around this issue, foster collaborative problem-solving between government and the fishing industry, and develop an action plan. I co-facilitated the workshop using foresight (a method from future studies). I featured the artworks from my Fulbright in the workshop space to serve as conversation starters and allow anonymous expression of views.

Photovoice-inspired artwork can evoke richer insight into complex issues, increase access to power by conveying local knowledge to policymakers, and emotionally engage participants and viewers in a way that could influence affective readiness for change

The workshop was successful. Participants created a draft action plan that all parties believed was acceptable for presenting and discussing with their constituents. The workshop evaluation showed that participants viewed the artwork favorably. Fisheries leaders even requested an exhibition of the artwork at a subsequent industry meeting. Additionally, one fisher adopted the PhotoVoice technique to create a narrative photo essay expressing his concerns to QDAF leadership, using a photo of a large hole in his treadless shoe to symbolize and communicate that he felt worn down and lacked the time, energy, and resources to replace his shoes let alone buy new camera equipment for his boat. His email yielded an atypically quick and positive response from QDAF that mentioned the artwork. This evidence supports the proof-of-concept that photovoice and photovoice-inspired artwork can evoke richer insight into complex issues, increase access to power by conveying local knowledge to policymakers, and emotionally engage participants and viewers in a way that could influence affective readiness for change.

Personal Impact of the Fulbright Experience

My Fulbright was transformative in that it affirmed my ability to create meaningful relationships and find community and my capacity to travel and explore despite my invisible disability. (I have Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, a connective tissue disorder that affects my mobility and often leaves me in pain, and a related condition that can make me dizzy and weak from prolonged standing or sitting.) My Fulbright also provided rich learning experiences of Australia’s people groups and cultures that have deepened my knowledge and provided a new framework for understanding sustainable practices.

In a post-pandemic world, where my network of friends and customary social gatherings had radically changed, I felt socially disconnected and concerned that it would be hard to build new social connections in my current life and career phase. So, I was relieved at how quickly I established a community of people I cared about, and who cared for me in exchange. For instance, I regularly had meals, took outings, and shared a laugh with my colleague and his wife, who also happened to be my neighbors. It was a joy to deepen our professional relationship into a friendship, which created a solid foundation and desire for future collaboration. I was an adoptive grandmother for the day when my pastor’s daughter asked me to attend Grandparent’s Day at her school because her grandparents lived far away in Sydney. My church community treated me like family, inviting me to their homes and showing care and concern when I was sick. I never felt alone during my stay. By the end of my Fulbright, I felt very comfortable in the life and relationships I had developed on the Sunshine Coast, and I often thought to myself, “I could live here.”

I sought out and built these connections in various ways. My Fulbright host held an introductory dinner party, where I met several people, who I subsequently followed up with to plan a coffee date. I often scanned the “What’s On” page of the local council and attended community events for Harmony Week, Reconciliation Week, Agricultural Shows, arts events, and weekend markets. I would invite someone I had met in the community to join me whenever possible. I also attended a local church and a weekly bible study at the pastor’s home. In addition, I joined a local gym. In these ways, I could start conversations with folks from many walks of life, from the neighbors in my apartment building to women in my Pilates class and vendors at markets. My American accent often made it easy to spark a conversation. There are several people who I got to know by meeting with them weekly. I treasured the opportunity to discuss current events, politics, cultural comparisons between the US and Australia, religious views, impressions of the area, travels throughout Australia, and, of course, my Fulbright project. I was struck by how open, frank, and straightforward Australians were. No topic was too taboo to discuss. Even when we had differing views, there seemed to be a sincere interest in hearing each other’s perspectives.

Travel was another highlight of my experience. My goal was to see every state and territory in Australia, but I was concerned that my disability would prevent this. Since my diagnosis, I had not attempted any significant solo travel, and certainly not the type of walking and hiking tours best for appreciating the vast Australian landscape. Thankfully, my hosts recommended skilled medical providers. I discovered that Australian airports are part of the Hidden Disabilities network, so even while traveling alone, I had aid and understanding of my conditions. With this support, I nearly reached my goal of touring the major cities in every state and territory (Western Australia was the exception) and saw the natural treasure of Australia’s wilderness. I walked in the Outback, along Tasmania’s shores, and saw a wild platypus and kangaroos. The experience so emboldened my exploratory spirit and confidence in traveling with a disability that I did a Fulbright Specialist project in Malawi and applied for the Fulbright-Hayes Seminar Abroad shortly after.

Wherever I traveled, I sought out cultural experiences, and I especially wanted to learn about and from the First Nations peoples of Australia. I learned about the history and culture of the traditional owners, the Gubbi Gubbi people, of the Sunshine Coast area where I lived during my stay. I learned to identify and eat local bush tucker and wove baskets with traditional techniques and materials. I passed on this knowledge to my mother and her friend when they visited, and they both returned home weaving baskets on the flight.

Two experiences struck me profoundly. I will remember them forever. I happened to be in Sydney for the last days of World Pride. I attended the Black & Deadly Gala at the Sydney Opera House, where I heard and saw a concert for the ages. I was unfamiliar with the artists, most of whom were from First Nations, but the spectacle sent chills up my spine and told me I was in the presence of world-class greatness. Deborah Cheetham sang an operatic indigenous welcome to country. William Barton gave a powerful digeridoo performance backed by the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. I later learned that they are living legends, and the line-up of talent was indeed a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

Also, while in Sydney, I went on an Aboriginal walking tour focusing on the Aboriginal saltwater people, their fishing practices, and their relationship to coastal species and habitats. I learned about their practice of environmental stewardship. In their culture, relatives note which plants are blooming or animals birthing at the time that a person is born. When that person reaches adulthood, they become responsible for the sustainable management and use of those plants and animals. This person cannot consume these species themselves but has the authority to permit or prohibit other people’s use of them. This traditional form of environmental stewardship ensures the species and the Aboriginal people who depend on them will continue to flourish. I have found this tradition so powerful that I have shared it with colleagues in the United States and elsewhere as a principle of personal responsibility and community stewardship that could inform and improve sustainable fishing efforts. In sum, my Fulbright was a phenomenal tour of Australian art, culture, and nature in my project and travels.

Notes

- Jenkins, L.D., Eayrs, S., Pol, M.V., Thompson, K.R, Uptake of proven bycatch reduction fishing gear: perceived best practices and the role of affective change readiness, ICES Journal of Marine Science. 2022, 0,1–10, fsac126, https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsac126.

- Araneo, P., Exploring education for sustainable development (ESD) course content in higher education; a multiple case study including what students say they like, Environmental Education Research. 2023, 1-28, https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2023.2280438

- Baldwin, C., Connor, S., Perez, E., Investigating social acceptance for the wild catch commercial fishing industry of Southeast Queensland, 2019, FRDC: Canberra, Australia. https://research.usc.edu.au/esploro/outputs/99450741402621

- Baldwin, C., Chandler, L., “At the water’s edge”: community voices on climate change. Local Environment, 2010, 15, 7, 637-649. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2010.498810

- Eayrs, S., Progress in bycatch reduction in trawl fisheries: Are the findings, outcomes, and recommendations from FRDC funded bycatch reduction projects acted upon? Final report to Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, 2019, Project No. 2019/082. Maroochydore. August. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354687736_Progress_in_bycatch_reduction_in_trawl_fisheries_Are_the_findings_outcomes_and_recommendations_from_FRDC_funded_bycatch_reduction_projects_acted_upon

- Rafferty, A.E., Jimmieson, N.L., Armenakis, A.A., Change Readiness: A Multilevel Review. Journal of Management. 2012, 39, 1, 110-135. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312457417

Biography

Lekelia Jenkins is an Associate Professor and marine sustainability scientist at Arizona State University in Tempe, Arizona. She received a Fulbright Scholars Award to Australia in 2023. This project was conducted in collaboration with Steve Eayrs, an Extension Officer at the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, and Claudia Baldwin, Lisa Chandler, Phyllis Araneo, and Lyris Snowden, faculty members at The University of the Sunshine Coast. Lekelia can be reached at Lekelia.Jenkins@asu.edu